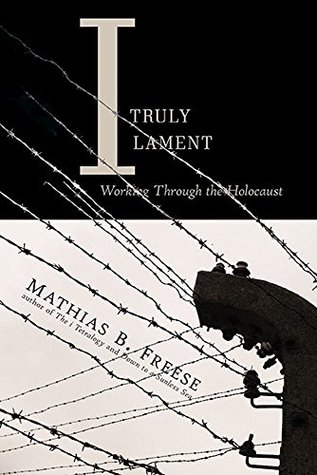

In this anthology, Mathias Freese has composed twenty-seven short stories about the Holocaust. They're an attempt to gain some form of understanding about it. In the Preface, Freese states: "All literary depictions of the Holocaust end as failures..." and "Every artist who struggles with the Holocaust must begin with an acceptance of failure, and that must be worked through before art begins." If I'm interpreting him correctly, the reason why all attempts end as failures is because no mere words on a page can ever truly convey what it was like to have been there. But nothing short of a fully immersive virtual reality program (and none has been created yet) ever could, so why set the bar so high?

In this anthology, Mathias Freese has composed twenty-seven short stories about the Holocaust. They're an attempt to gain some form of understanding about it. In the Preface, Freese states: "All literary depictions of the Holocaust end as failures..." and "Every artist who struggles with the Holocaust must begin with an acceptance of failure, and that must be worked through before art begins." If I'm interpreting him correctly, the reason why all attempts end as failures is because no mere words on a page can ever truly convey what it was like to have been there. But nothing short of a fully immersive virtual reality program (and none has been created yet) ever could, so why set the bar so high?

I'm not sure why Mr. Freese wrote this book. A tribute to the dead? The survivors? He states that: "No piece of art...can ever expunge the Holocaust." To which I rather flippantly say, "Well, duh." If this was ever his intent, it's a fool's errand. But no, this is an attempt to "work through it" despite his insistence that: "We will never work it through."

So it was after reading this conflicted preface, written by a man who so desperately wants answers to the questions he poses, that I read this book.

Obviously, this was no beach read. Rather than compose these stories as entertainment (Can the Holocaust, or any genocide for that matter, ever be formed into entertainment?), they're more like twenty-seven fictional biographies. Alas, they're repetitive. There were three stories involving golems. There were several stories each about Jews fleeing Nazi pursuers, life in the camps, and survivors trying to eke out some kind of life afterwards. While each was slightly different, too many elements were the same. For instance, all but one survivor story took place in Tuscon, Arizona.

But there were stories that broke out of the mold. "Max Weber, Holocaust Revisionist" was more of an essay. Freese explains that when he was writing a story he was derailed by a historian's contention that the Nazis did not make soap out of Jews. Freese researched the historian and learned that the man was a historical revisionist. Freese submitted his The i Tertralogy to him for a book review and published it herein as "Sincerely, Max Weber". I'm assuming both are true. Freese skewers the man in a story entitled "Soap", one of the best stories in the collection.

There are two fictional interviews: "Herr Doktor" and "Der Fuhrer Likes Plain". Both of these were among the better stories. The first one is an interview between an American doctor and a camp doctor. The interviewer is trying to determine at what point the camp doctor lost his ability to follow his Hippocratic Oath. The latter story is a fictional interview with Eva Braun just a few days before her death in Hitler's bunker. While it got off to a good start, it veered off into details about Hitler's sex life that have been gossiped about but never substantiated.

"The Disenchanted Golem" starts out with a golem discussing a few events over the course of his incarnations and what it's like to be a golem. But midway through his conversation with the reader, he tells us about the one he has with a rabbi. It has a bit of a Pinocchio quality to it, but without the Disney effect.

My favorite story was "Cantor Matyas Balogh". The titular character meets a woman in a sweets shop, and the two strike up a conversation. The conversation leads to tea and then to romance. It's a story about finding love when the world is going to hell. Both are aware of the dangers around them, but continue on because love has a power all its own.

In summary, I Truly Lament is a collection of stories centered on the Holocaust. While there are many repetitive story elements, individually, they offer poetic glimpses into the brutality endured. There are standout stories that rise from the miasma of the subject matter. It is a difficult read at times, for the subject matter and the associated suffering can be a bit much. If you can separate the entertaining tales from the pseudo-biographical cathartic soliloquies, then this book could be for you.

For more information about I Truly Lament and Mathias Freese, please visit his website.

This book has been getting a lot of attention online, so I was eager to read it. It is the story of a dysfunctional family, the sons and daughters of Holocaust survivors. Although it purports to be the story of the matriarch, information about her is relatively sparse and leaves the reader with many questions.

This book has been getting a lot of attention online, so I was eager to read it. It is the story of a dysfunctional family, the sons and daughters of Holocaust survivors. Although it purports to be the story of the matriarch, information about her is relatively sparse and leaves the reader with many questions.