When

the body of Harry Injurides - playwright, provocateur and bodybuilder - washes up on a beach, his

friends are shocked, but not altogether surprised. But when they meet to mourn Harry, he shows up

and says he's been resurrected.

When

the body of Harry Injurides - playwright, provocateur and bodybuilder - washes up on a beach, his

friends are shocked, but not altogether surprised. But when they meet to mourn Harry, he shows up

and says he's been resurrected.

Pharoni is the story of those friends. Tommy Pharoni tries to overcome his shock by writing about his friend's resurrection, and accidentally starts a religion. Roy Sudden starts a tech empire based on digital empathy and digital pain, drawing in billionaire investors, femme-fatale programmers, and tsunamis of capital. And, Roy's on-again, off-again girlfriend Maud works in secret to bring radical justice to the most neglected and abused corners of society.

As Tommy's religion grows, Roy and his backers try to take control of it. The battle, about more than doctrine, engulfs Tommy's marriage and threatens his life, leading to a conflict with strangely humane results that no one could predict.

Told in the first person, Pharoni has the feel of a memoir or a really long confession. Tommy Pharoni is a struggling screenplay writer who pays his bills and alimony by working a soulless marketing job. His closest friends were aspiring artists of different sorts in college. Now in their mid-thirties, they've set aside those aspirations to "adult" properly. All except for Harry, whose death opens the story. Harry struggled to fit into contemporary society, instead preferring to help the homeless while penning "words of wisdom" in his many notebooks. After his death and subsequent re-birth, those notebooks wound up in Tommy's possession. Ultimately, Tommy would collect them into a coherent manuscript and seek out a way to get them published.

As Tommy is a screenwriter, the format of the story periodically shifts into screenplay mode. This works particularly well for conversations as it affords opportunity to get to know the other characters through their dialogue rather than relying on Tommy's narrative. I wouldn't say Tommy is an unreliable narrator, but he does limit what we can learn about what's going on elsewhere with other characters. References to things that have been written elsewhere and NDAs force the reader to fill in the gaps.

After Harry's resurrection, the lives of Tommy and his friends change as described in the blurb, but there's so much more. The group of friends find themselves splattered by the seven deadly sins, fitting for a story where a religion is founded upon the philosophical musings of a character that has died and miraculously resurrected days later. At least Christianity didn't get partnered with a health and wellness brand. The corrupting influence of millions and billions of dollars seeps its way into their lives and rots them from within. What is friendship worth? Can you put a dollar amount on it?

If there's one overarching theme that I can take away from this tale, it's that power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Keeping this spoiler free, I'll say that Tommy started out as a character that I could connect with to someone I didn't want anything to do with. But I stuck with him because act two opens with:

This is where I get unrelatable, maybe even unlikable. As the writer of failed screenplays, I know what a mortal sin unlikability can be.That gave me hope for him in act three. But Tommy is far from the only person to be corrupted by power. It's everyone up to the very end of the story. And the only characters whose souls are left intact are those who never possess it.

Colin Dodds has crafted an excellent morality play with vivid characters. Pharoni offers modern day parallels to the founding of Christianity, right down to the Christmas star, but in an age of unbridled capitalism. If you're old enough, with all of the life experience that implies, it forces you to take a look at this fellowship of friends and how they sacrificed art and friendship for wealth and power and check to make sure that this isn't a mirror of your own life.

4 stars

\_/

DED

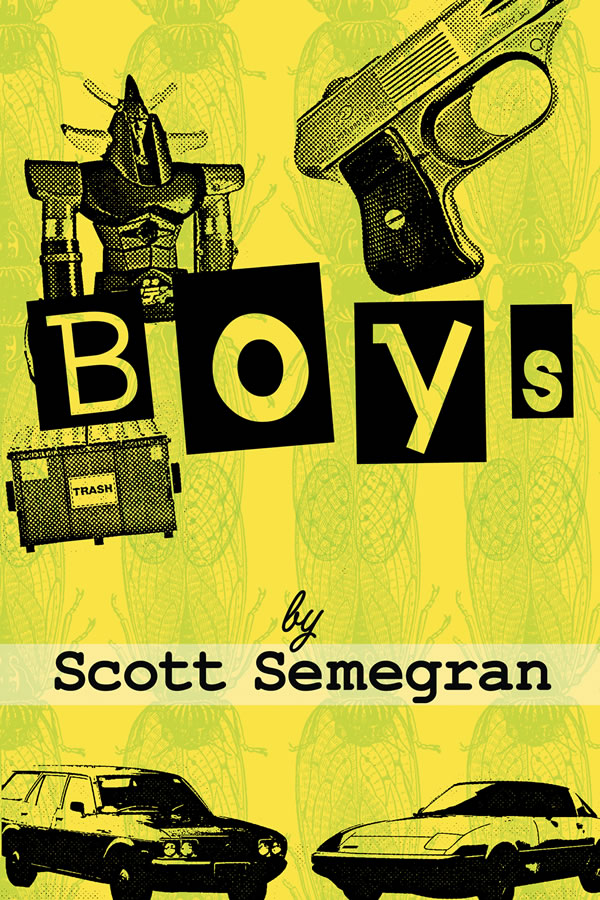

These are the stories of three boys living in Texas: one growing up, one dreaming, and one fighting to stay alive in the face of destitution and adversity. There's second-grader William, a shy yet imaginative boy who schemes about how to get back at his school-yard bully, Randy. Then there's Sam, a 15-year-old boy who dreams of getting a 1980 Mazda RX-7 for his sixteenth birthday but has to work at a Greek restaurant to fund his dream. Finally, there's Seff, a 21-year-old on the brink of manhood, trying to survive along with his roommate, working as waiters and barely making ends meet. These three stories are told with heart, humor, and an uncompromising look at what it meant to grow up in Texas during the 1980s and 1990s.

These are the stories of three boys living in Texas: one growing up, one dreaming, and one fighting to stay alive in the face of destitution and adversity. There's second-grader William, a shy yet imaginative boy who schemes about how to get back at his school-yard bully, Randy. Then there's Sam, a 15-year-old boy who dreams of getting a 1980 Mazda RX-7 for his sixteenth birthday but has to work at a Greek restaurant to fund his dream. Finally, there's Seff, a 21-year-old on the brink of manhood, trying to survive along with his roommate, working as waiters and barely making ends meet. These three stories are told with heart, humor, and an uncompromising look at what it meant to grow up in Texas during the 1980s and 1990s.

Surgeon Robert Emmerling’s death at age 86 in The Girl in the Photo’s opening chapter serves as a catalyst for a series of discoveries by his two children. While clearing out their father’s home, David and Abbie find a memoir he had written about being stationed in Japan during the Korean War, years before he met their mother. It describes his involvement with Masami, a woman he met there. David and Abbie also turn up Masami’s photograph and a letter she had written to Dr. Emmerling after he returned to the U.S. This previously unknown episode in their father’s life raises questions for the siblings: Why did the romance end, and what happened to Masami afterward?

Surgeon Robert Emmerling’s death at age 86 in The Girl in the Photo’s opening chapter serves as a catalyst for a series of discoveries by his two children. While clearing out their father’s home, David and Abbie find a memoir he had written about being stationed in Japan during the Korean War, years before he met their mother. It describes his involvement with Masami, a woman he met there. David and Abbie also turn up Masami’s photograph and a letter she had written to Dr. Emmerling after he returned to the U.S. This previously unknown episode in their father’s life raises questions for the siblings: Why did the romance end, and what happened to Masami afterward?

Legend has it

that Shakespeare's play, Macbeth, is

Legend has it

that Shakespeare's play, Macbeth, is

As it is October,

I decided to find something dark in the slush pile. The Cloven fits the bill.

As it is October,

I decided to find something dark in the slush pile. The Cloven fits the bill.

"By 2010 President Obama was constantly looking for terrorist in every corner of the globe. While cities and towns in the United States crumbled, Chinese computer programmers began to create a virus that paralyzed the weapon systems in the U.S. All combat took place hand to hand, gun to gun. The people of the United States were not particularly patriotic during that time so it was easy for the Chinese military to occupy the U.S."

"By 2010 President Obama was constantly looking for terrorist in every corner of the globe. While cities and towns in the United States crumbled, Chinese computer programmers began to create a virus that paralyzed the weapon systems in the U.S. All combat took place hand to hand, gun to gun. The people of the United States were not particularly patriotic during that time so it was easy for the Chinese military to occupy the U.S."

and

and

Available from

Available from